El Otro 11 de Septiembre

Much has happened in just half a week! Where to begin…

Tuesday we had our first “temblor”! Around 7:25 a.m., I woke up to my bed shaking and realized I was experiencing an earthquake. I didn’t feel scared honestly. I think David put it best when he said, “It kinda felt like I was being rocked to sleep like a baby…I kinda liked it.” Turns out it was a 4 on the Richter scale, so noticeable, but not life-threatening.

Normally, David, Austin, and I would be running at that time in the morning, but we had decided to do a long run in the afternoon to ascend “Cerro el Carbón.” The initial intent was to trail run up this thing, but it was just too steep. It took an hour to reach the top, and I think only around 12 minutes of that were actually running, the rest swiftly hiking. But the view was incredible! We were higher than the Costanera Center and had probably the best view of Santiago we’ve gotten so far (and we’ve had some pretty sweet views).

I returned home exhausted and dirty, but was quickly cheered by the family and the usual humor. Paula, Roberto, and I watched a particularly amusing episode of Caso Cerrado. A female rancher from Texas was asking for $60,000 from her neighbor. The rancher has a wall on her ranch that borders Mexico, and her neighbor had supposedly been giving illegal Mexican immigrants the access code to cross it. The rancher also demanded $150,000 to construct a bigger and better wall. The judge was just baffled – how on Earth had the US government allowed this rancher to have control over a border wall, code access and all? The neighbor just kept calling the rancher a racist, and we all agreed that the rancher wasn’t being unreasonable by saying the immigrants are illegal and she could get in huge trouble. She ended up receiving only the $60,000. It was just a lot of funny yelling, confused looks by the judge, and Roberto telling Paula, “Shhh! Lemme listen!” Meanwhile, Clarita was in the kitchen, getting more frantic than she already is, revved up by our laughing. She received an injection yesterday at the vet to help her back, and she’s been ordered to rest for 10 days – meaning no fetch or walking up stairs. Which will be impossible for that little ball of energy.

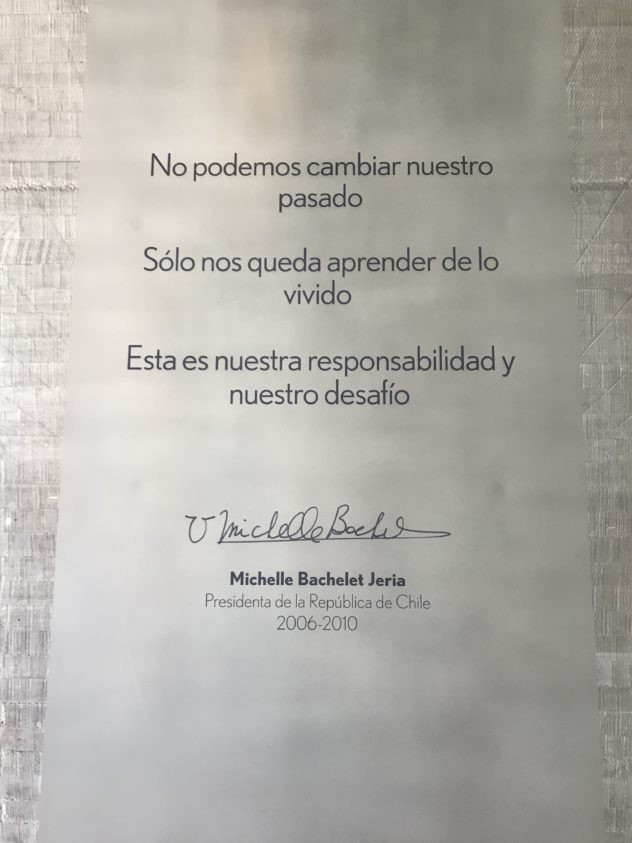

Today we went to the Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos, a tribute to all those assassinated, exiled, disappeared, or tortured during Pinochet’s dictatorship. The experience was heavy, but I also had a lot on my mind. On Monday, Paula had openly talked about the years of Allende and Pinochet, unprompted, and I learned so much.

We were watching TV, and on the news were reports of a protest on the highway. Like EZ Pass in the US, there are tolls on the Chilean highways that automatically charge you as you drive through. The toll fees have just continually gone up, and there’s no limit to their increase because the toll company is owned by the Spanish. Thus, the money charged to drivers isn’t going back into the Chilean government and economy. The protesters were not only protesting the high costs, but the discrepancy between the costs and service provided – the highway is very slow, so they’re paying a lot to arrive late to their destinations. Paula says there are similar problems with high electricity, water, and copper costs; foreign businesses have control over all three, so they can raise prices without limit.

I stopped her: “But didn’t Allende nationalize all copper mines during his presidency?” “Yes, he nationalized the copper mines that existed then. Since then, foreign mining companies have moved in.” This was her gateway into discussing Allende and Pinochet.

“You’re going to the Museo de la Memoria on Wednesday, and I just want you to hear the other side. People always paint Allende as the hero. And yes, he did do good things for Chile. But things were just as hard under his presidency as Pinochet’s. There was nothing. No food, no gasoline. Cars could cost as much as a house. My father was a Socialist, and so my mother was constantly afraid that he might be arrested. Luckily, he was only a Socialist in thought, not action, so he never was. Before Allende, Roberto’s father was pretty well-off. They had two farms, with lots of animals and crops. Once Allende became president, their farms were expropriated to a bunch of farmers – who didn’t do anything productive with the land – and so Roberto’s family became quite poor. Many families like his left Chile, and that’s why there was no more production of anything. By the time Pinochet rose to power, the farms had been converted to a co-op, so Roberto’s family couldn’t take back full control of them. I know that many bad things happened under Pinochet’s rule. I don’t mean to undermine all the people whose family members were tortured, murdered, or disappeared. But Pinochet did restore our economy. Yes, I didn’t get to go out to ‘fiestas’ since he imposed a curfew, but the streets were quite safe.”

“At this point, I consider myself a little right of center, politically. But I can’t express these views because I’m immediately called a ‘Pinochetista.’ And it’s unfair because the leftists here make such a fuss and I always listen to them. Like I said, my father was a Socialist. My sister, who lives in Bolivia, is a Socialist. She has four houses, which goes back to why I say there are no poor Communists. But I listen to them, and they never listen to me. And I think Allende caused this division in our country.”

“I look to countries like Venezuela – they’re experiencing what we did under the dictatorship and are fleeing to us. And in Cuba, they’re living the way we did under Allende.”

“I try my best to always see the good and the bad to everything. But here, people just see the bad of Pinochet and the good of Allende. And that’s what I wanted to tell you before you go to the museum.”

As you can imagine, I sat down and furiously recorded everything I could remember Paula had said. I wanted to have it as a reference, always, in these conversations in which we praise Allende so much. Hearing both sides is invaluable, and as a CC student, I’m constantly hearing only one side, the liberal side. I kept Paula’s words in the back of my mind at the museum.

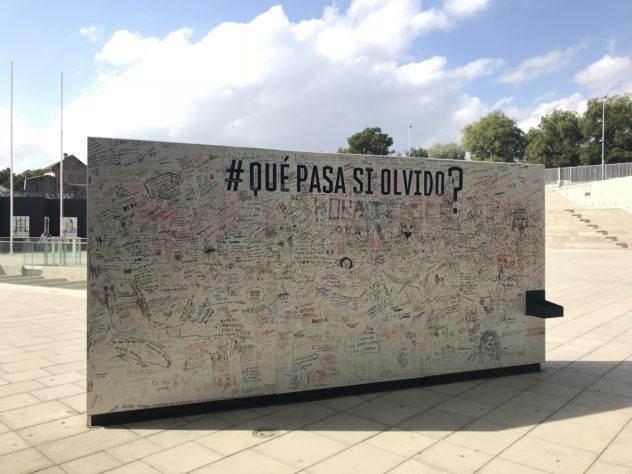

The museum itself has a lot to offer. We were given a guide, which meant that we breezed over a lot of its content, but it also kept me from getting overwhelmed by the sheer volume of exhibits. We began at a large wall that has a map of the world made up of photographs. The photographs correspond to countries, and each country has information about periods of severe human rights violations and the committees that addressed them. In Chile, for example, there was a commission that assessed murders under Pinochet and a commission that assessed torture and political imprisonment under Pinochet.

Our guide reminded us that it’s only been 45 years since the military coup. Wounds are still very, very fresh. Upon initially opening the museum, it was difficult for employees to deal with visitors who continued to deny the human rights violations and to support Pinochet. Luckily, the location of the museum isn’t additionally triggering; it’s located in a section of the city unrelated to anything involving the dictatorship.

The first room is dedicated to that day of the military coup: September 11, 1973. I was very impressed by this room, as it had a timeline starting at 6 a.m. that day, noting all the announcements made by Allende on the radio and key events that passed hour by hour. We watched the film of the planes bombing the Moneda, and simultaneously could look at a live feed of the Moneda, peacefully untouched. Our guide asked, “Why bomb the Moneda? Why was it necessary? Because of its image. It made a statement that things wouldn’t be the same.” Overhead, you could hear Allende’s announcements, including his last words. If you have time, look them up. They’re incredibly powerful and eloquent despite being totally improvised.

We continued on to a more detailed timeline of the years that followed the coup. Pinochet was Allende’s top general, and he betrayed the Socialist president. In his years of power, a new constitution would be written and new commissions controlling school and government pensions would be formed – things that remain today. We watched a German news report of the military coup, which was interesting given the outside perspective. What struck me most was how sudden it all was; the video noted, “The myth of ‘apolitical’ soldiers had ended.” Pinochet’s troops immediately took to the streets, forcing citizens to surrender all possessions related to Communism, Socialism, or Marxism and to paint over all leftist propaganda. They burned leftist books, but out of ignorance, burned precious materials. Any books about “cubism,” for example, were burned because of their supposed relationship to Cuba. Any books with the word “revolution” on the cover were burned, even “The Industrial Revolution,” or “Math Revolution.” And so many Chileans destroyed or removed the covers of their books so they could still read them without others knowing their content.

The day Neruda died, Pinochet’s newspaper, El Mercurio (still the most prominent today), gave the poet a small section and picture on the front page, nothing close to what he deserved. Pinochet replaced many school directors and curriculum was rewritten. 200,000 writers, poets, artists, and musicians fled Chile in exile. Not only was Pinochet denying Chileans their culture, but he was denying them of a nationality. He claimed that he was not punishing “ideologies,” but law-breaking. Naturally, many took refuge in various embassies, as foreign countries stood with Chileans in solidarity.

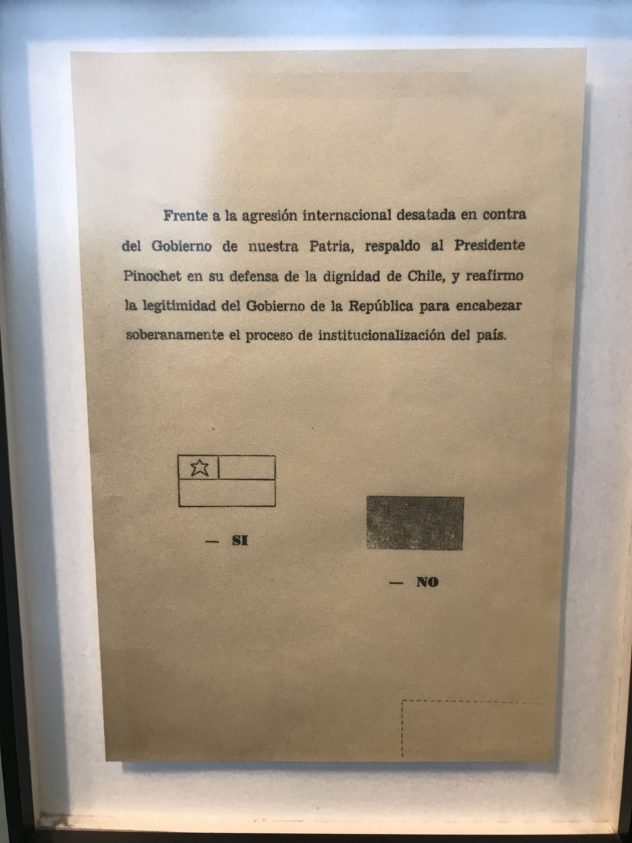

What was quite despicable was seeing the ballots for the first referendum Pinochet issued, which was a vote to declare him a legitimate president. He issued tons of propaganda on TV saying that a vote against him meant a vote against the country. On the ballot, the “yes” to Pinochet was a box under a small Chilean flag, the “no” a box under a black banner, which was also placed lower on the page. The only evidence that you voted on this referendum was a sticker you received saying, “I voted.” Of course, people could then easily cast multiple ballots and the numbers were distorted. However, most were ignorant that the government had no record of their identity along with their votes. Out of fear, they voted yes to Pinochet, even though no one would have known if they had voted no. 75% of voters apparently voted “yes.”

Further into the museum, we saw several meaningful walls. One, a map of Chile illuminated with all of the detention centers. The vast majority were in Santiago, but they spanned the whole country. Another wall listing all the names of those tortured during the dictatorship – and counting. And a wall of pictures of all those murdered or tortured or exiled or disappeared during the dictatorship, donated by the victims’ families. The wall has many blank picture frames to keep adding to the wall, and it’s all in black and white.

I felt much the same way I did after visiting a concentration camp in Germany. Heavy, mixed up emotions, that I’m still processing. Chileans are doing the same.

On a lighter note, my dear friend and roommate from first semester, Hannah Schultz, is here and saw the museum as well. She’s doing a non-Colorado College program in Arica, which is the furthest north you can get in Chile. The program is all on public health, and they’re in Santiago for 5 days learning about health care in the big city. So good to see her and catch up over ice cream and dinner!

Much more to come this week – Dani’s gig tomorrow night, volunteering with at-risk Chilean youth, climbing in Maipo, and maybe introducing Hannah to a terremoto (the drink, not the natural disaster)! Stay tuned.