Project Overview

Our original grant proposal:

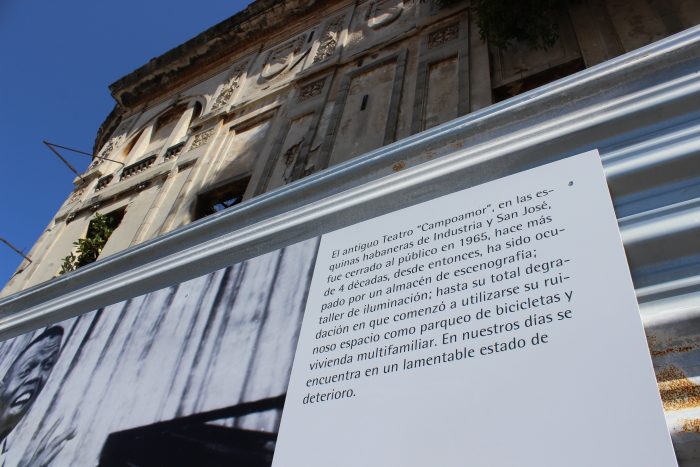

When advertising trendy vacations to Cuba, every article describes old cars, bright but crumbling buildings, blissful island vibes, and music pouring onto the Malecón. Countless media outlets, including the New York Times, describe Cuba as being “a time capsule” and “on the cusp of change.” American tourists, previously unable to visit, lament wanting to visit before the country is “ruined” by capitalism. Visitors leave Havana with a distorted view of socialist society, viewing daily hardships through rose-colored glasses. As stated in one opinion article, “For these Americans, Cuba exists solely as an idealized socialist paradise, in almost complete stasis since the Cold War, which has yet to be befouled by the corrupting influence of other Americans. For them, the island nation is the land of the noble savage on the verge of contact with the advanced but impure outside world, sure to despoil its backward, but charming, ways. These people don’t want to see the real Cuba. They want to be able to say that they were there before it got Americanized.” But what is the reality of Cuban life, and how can we, as visitors, be aware of our positionality and participate in ethical tourism?

As a student of CC’s Latin America Program in Cuba, I certainly lived a charmed life in Havana — beautiful island weather, a loving host family, laundry done for me, and meals provided or bought cheaply made life seem simple. It’s easy for me to look back fondly of my time there. I fall into the trap of what psychologists call “rosy retrospection” — because my experience as a whole in Cuba was positive, I talk of my time there more positively now than when I first left. This effect only grows with time and distance. The reality is, I confronted daily the harsh truth that my idyllic life was at the expense of constant hardship for the Cubans around me. My host mom Angelita did not serve us spaghetti until my last week because she insisted she needed to serve it with cheese; however, she had not received any cheese rations in ages and she could not purchase it because all the restaurants had been buying it up to serve to tourists. She would not go out to buy food, or “comprar comida”; she went out to look for food, or “buscar comida.” While Angelita does reasonably well financially, serving tourists, the reality is most Cubans, on average, earn $24 a month. And because the economy is so reliant on tourism, taxi drivers are earning more money than are doctors or teachers. This has created a paradox that illustrates tourism as a double-edged sword. While access to the tourist economy has greatly improved the lives of many Cubans, it has also made things, like basic food items, even more inaccessible for others.

Ironically, despite these struggles, tourists still romanticize the Cuban people and their country. There is a strong belief of “resolver” in Cuba: the sentiment that no matter how difficult life becomes, all will be resolved. Thus, hardships are framed in a deliberate way. Long lines waiting for food, internet cards, or money are “worth the wait;” having limited access to internet (which is also highly censored) allows people to be “disconnected” and focused on face-to-face interaction; as a result of the Revolution, most basic rights (such as healthcare, education, food and shelter) are free, but often extremely lacking in resources. Meanwhile, tourists don’t even realize the underlying stress Cubans endure dealing with these issues on a daily basis, instead fixating on white sand beaches and shiny vintage cars.

The romanticization of Cuban life presents a form of cultural imperialism — as Americans, it is easier to view Cuba as a sort of “Cold War museum,” rather than assessing our own role and effect on Cuba’s economy. As a psychology student who has studied the phenomenon of “rosy retrospection” and had the opportunity to spend several months in Cuba, I hope to examine myself and my own viewpoints in the context of broader experiences. I believe I can learn to engage with the tourist culture in Cuba in such a way that appropriately supports the Cuban economy while also recognizing the problematic role I play within it. Through this, I hope to answer several research questions:

- How is Cuba viewed from a global perspective? How is it idealized in a damaging way?

- How does this affect tourist experiences and local psychology?

- How does this affect return?

- Is tourism damaging or helpful?

- How is my presence problematic?

- How can I engage in a way that is self-aware?

To conduct this research, I want to interview many people, the first being tourists. I’m curious to hear their impressions of Cuba — have they been before? Why did they choose to come back? What do they think they’ll remember most from their visit? Perhaps tourists from different parts of the world will be more or less cognizant of the social issues in Cuba, or perhaps they will all point to the classic 50s cars and “son cubano” reverberating in the streets.

Next, I’d like to speak with those with a similar experience to mine: CC students from the Latin America Program, specifically Mitra Ghaffari and Lucy Marshall, who have lived for a prolonged period on the island. In what ways do they sense solidarity with Cubans, and in what ways do they feel permanently estranged? How do they reconcile the economic and social discrepancies between themselves and their Cuban friends? Does it deter them from staying, or compel them to return?

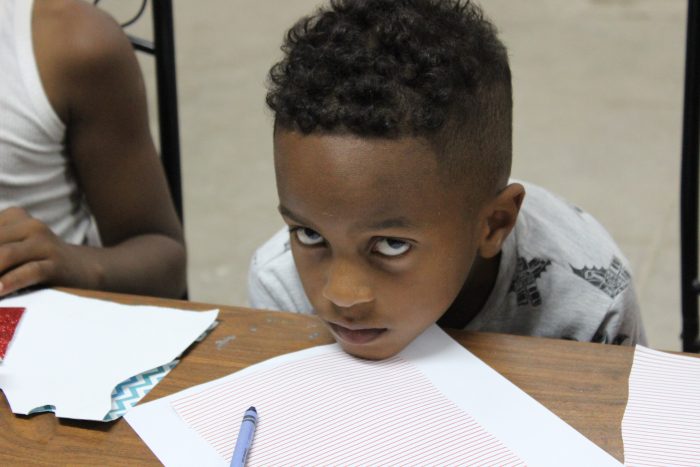

Finally, I must talk to Cubans themselves. What do they think of tourists? Is everything just one grand show, or do they genuinely like engaging with foreigners? What do they wish they could change about tourism in Cuba, and what do they appreciate? I’d like to speak with Cubans from all neighborhoods — not just Old Havana (tourist town), but also Vedado, my home neighborhood and business/family district, and Los Pocitos, a marginalized neighborhood in which the Semester in Latin America students have volunteered. In addition, Evyn Papworth, the Political Science paraprofessional, will also be in Cuba and join me for the project. She has spent significant time in Havana as an alumna of the CC Latin America Semester and as a recipient of the Davis Project for Peace Grant. Her connections within Havana will greatly help me conduct my research.

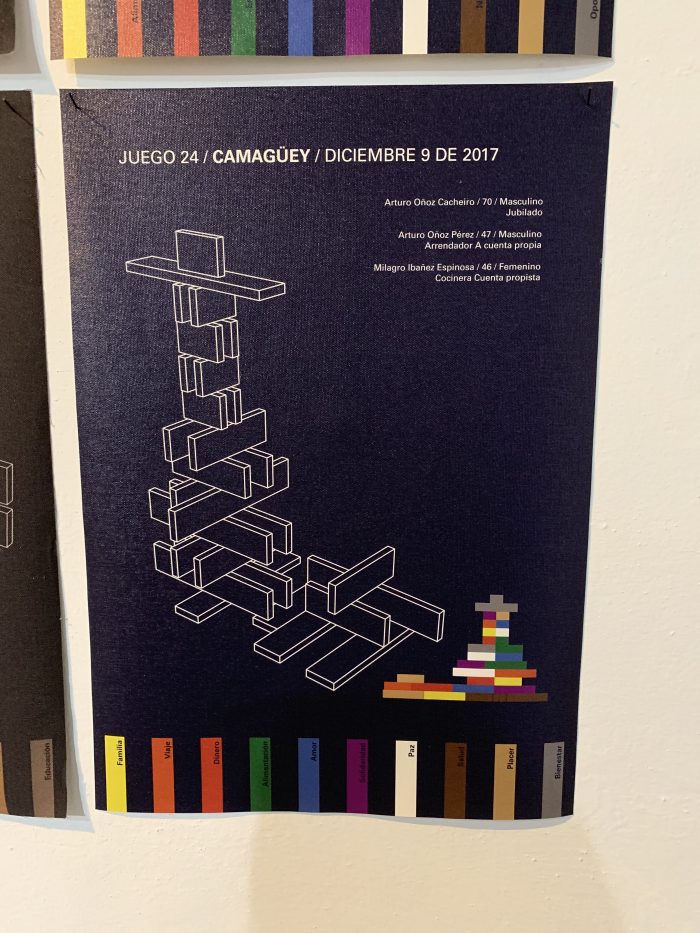

The project will be divided into four themes, one per day: Disconnectedness, Aesthetics, the “Authentic” Experience and Cultural Imperialism, and Ethical Tourism and Daily Life. Each day will encompass interviews and site visits as well as relevant readings related to the theme.

As a psychology major, this project provides me with valuable experience conducting fieldwork to better understand and apply academic theory. This project is also uniquely personal, because I have been guilty of this same romanticization. By getting a broad range of perspectives, I can better understand the ways in which my presence is problematic and how I can best engage in a respectful way that recognizes my privilege and does not patronize Cuban society. This personal growth translates to a wider international scale, and seeks to evaluate the way we as Americans interact with Cuba, and how this is indicative of our shared oppressive history. The island is not a museum, and deserves to be approached from an informed, self-aware perspective. Rosy retrospection, while beautiful and nostalgic, does not paint the full picture. By seeking to engage with Cuba through a more respectful tourism, we can begin to change our imperialist relationship.