Day 1

Returning to Cuba was a lot like returning home.

We touched down in La Habana at 9:30 p.m., the lights of the city less all-consuming than that of most cities. Our American pilot griped about the lack of gates — as if waiting for a gate were uncommon at any airport — and the Cubans around us remained stoic, accustomed to waiting. We de-planed and made our way through Jose Martí International Airport, the humid Havana air feeling welcome, the painstaking lines through immigration, baggage claim, customs, and currency exchange received with resignation. When at last we found ourselves seated in a taxi racing toward the city with our gregarious driver bumping and singing along to Ozuna, we felt at peace.

We met our friend Mitra at her apartment on Calle 23. She lives essentially on the border of two neighborhoods, Centro (University district) and Vedado (business district), and has been working as an editor for Prensa Latina. It was nearly midnight, but we remained up and talking for a short while, discussing the travel and Mitra’s experience thus far being back.

Though things are largely the same on the island, the lack of resources has grown. Mitra explained that Cuba is entering a second “Special Period” of sorts. In the 90s, the Special Period was an era of extreme shortages of food and basic necessities. As tourists continually consume the best resources available, Cubans struggle to meet their own needs. Their struggle is exacerbated, Mitra says, by Venezuela’s practically destroyed economy. Now that Guaidó, a democratic president, may fully assume power over socialist Maduro’s Venezuela, Cuba may lose the support of the fellow socialist country it relied on most. Which would spell even larger problems for the country. Mitra explained that Cuban television has essentially covered up all the problems in Venezuela, only presenting positive news — if there is any — coming out of the country.

We already felt the the effects of the shortages the next morning. Mitra had mentioned that eggs were recently scarce, and sure enough, one of our favorite cafes lamentably had none to provide some of their best dishes — arepas and tortilla. We still had a very tasty and filling breakfast, but it was discouraging to already encounter a shortage.

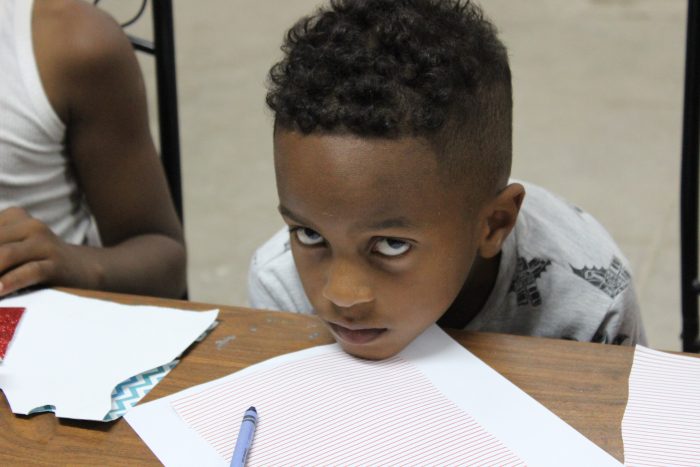

After breakfast, we headed down Calle 17 toward the communication center, ETECSA. The humidity was picking up steadily, and we found ourselves in an all too familiar situation: asking who was last in line (el último) and proceeding to wait in line (hacer cola) for a long time. I approached a friendly woman fanning herself while a young girl with her sat on a nearby bench. I explained the situation — we’re Americans here studying tourism in Cuba, could we ask her some questions? With every word of Spanish I spoke, her smile grew wider and her eyes grew brighter.

Evyn presented the perspective of most tourists toward the lack of internet in Cuba: “Oh, I love being disconnected!” They fail to recognize that lacking internet can be a real hardship for Cubans trying to access information, contact family, and get work done. However, this woman, Rosalia, didn’t seem to mind; she noted how tourists, in their home countries, consume, consume, consume. With limited internet in Cuba, she has the ability to be in contact with friends and family, but she’s not constantly checking things. In her view, life in the US is very “rápido, agitado” and for that reason, it makes sense that US tourists would want to disconnect.

Rosalia herself doesn’t interact much with tourists, being in Vedado. She’s content in Cuba, as it’s very safe. Children play in the streets without worry. Internet is improving, and 4G may arrive on the island soon. Would she leave Cuba? Perhaps to visit her daughter in Texas, or another country such as Spain. But she wouldn’t live anywhere else. And with that, she hurried into the air-conditioned ETECSA to take her turn and buy a WiFi card.

I sat down on a bench while Evyn headed inside after her. An older gentleman approached me, speaking half-Spanish, half-English, asking me if I was from New York. He must have heard me telling Rosalia. In any event, he said that he had grown up in Queens and his name was Sergio. His New York accent was subtle, but there. As we got talking, I learned that he had trained to be a surgeon in Cuba, and has been in and out of the country since the years of the Revolution. He has traveled the world as a surgeon and, now retired, recently bought an apartment in Cuba. He elected to make it his home base, but he still wants to travel, particularly to Peru, where he was born.

Evyn returned to us in conversation and introduced herself. We explained our project and he offered us his card, saying we should come by his house that week to check out some related books that he thought we’d enjoy. Then he thought better of it and just said, “You know what? I just have to get an internet card. Why don’t you all come back to my place now? It’s very close. My wife also speaks English. Then you can take pictures of the books.” He turned to go inside the ETECSA and it seemed he’d already decided we’d agreed. And so we went.

We walked north toward the Malecón (coast), and arrived at a tall apartment building. He took us up 18 floors to his lovely apartment, where his Cuban wife, Rosa, was watching TV and tasking a younger guy with rearranging some bookshelves. Sergio took us out to his balcony where he had a stellar view of Havana and a delicious breeze. Rosa immediately went to fussing over us, bringing us water and fresh guava juice, offering ice cream, too.

Evyn and I sat down in rocking chairs with Sergio on the balcony, sipping juice and relishing the breeze. My first question for Sergio: “You’ve been traveling the whole world your entire life, and you chose, after retiring, to settle here. You made Cuba your home base. Why?”

Sergio explained that as a person, he’s just not accustomed to staying in one place. Though he’s settled here, he’ll still travel in and out. He came to Cuba for the first time in the 60s and ended up going all over the world, so perhaps living in the US was “for naught” after being being born in Latin America. Regardless, whenever he left Cuba, he’d hear “the most incredible things” about the island, which weren’t true. So, he tried to give people the reality of Cuban daily life.

He’s watched the country change immensely. He brought up the Special Period, saying that up to that point, Cubans were living under a practically artificial economy. There was no hunger, no homelessness. Free education and health care. And these are the things that Cubans always point to when you try to critique the Cuban government. Sergio believes that because the Cuban people were always very nationalistic, challenging their country’s principles “flexes” them. They’re used to Fidel’s rhetoric of comparing Cuba to capitalist countries and how it’s better. Still, Cubans are obsessed with northern culture — our movies, our music, etc. Sergio respects the triumphs of the Revolution, but he’s quick to remind Cubans that a lot of their “inventions” are things that have already been created. They’re behind.

Several times, Sergio pointed to a “top-to-down” perspective of Cuba, worldwide. I interpreted in this in the psychological sense: in top-down processing, you make an immediate assumption about something you’re examining, then look to its details to corroborate that assumption. People assume that because Cuba is a socialist country, it must not function well, so they then point to all the reasons why this is so. On the other hand, in bottom-up processing, you take in the details of something one at a time until you form a sensible understanding of it. By using top-down processing, people are quick to say Cuba made a mistake going socialist, Sergio says. Rather than taking in the positives and negatives of the system individually.

Sergio thinks that Cuba is unlikely to relinquish its grip on socialism. If anything, the embargo has united the Cuban people more and more, and succumbing to any other sort of system will mean losing their power to some other country. Cuba was the first country to come out of the control of the United States during the Cold War; it’s proud of that. He iterated several times that the development of Cuba is just one of the reasons he studies history. He finds his life enriched greatly by history and is always seeking to find the truth, especially in this age of censorship and distortion.

After the interview, Sergio puttered around the house in search of countless books, while Rosa stood guard against him messing up her new bookshelf organization. Satisfied with a large stack, he placed them before us to photograph, making comments on each. Finally, he requested some selfies with us before we departed for the Malecón.

We made our way to the coast and walked west, watching the waves crashing the shoreline. Pausing briefly to check email outside the old hotels, we couldn’t help but feel that we had never left.

Next, we headed up our favorite street: 6. Calle 6 is home to many favorites: the juguería (juice shop); live music at the Bombilla Verde cafe; John Lennon Park and Submarino Amarillo; Casanoba, our favorite cafetería; Vampirito, the best pizza place; the stand with our local churro guys. But most of all, it is the street where our host parents, Angelita and Silvino, live.

We’ve walked 6 countless times and could never tire of it. Arriving at the red gate of their house, bearing “Angelita” in mosaic tiles, we couldn’t contain our excitement. Silvino buzzed us in, and in no time, we were back chatting with our Cuban grandparents.

They looked well; the house was clean and beautiful as ever, but had been renovated a bit with new grates along the windows — government order, for security. Silvino looked positively stylish in a pair of fresh New Balances, white-washed jeans, and a Hollister t-shirt. Angelita, on the other hand, was wearing a knee-length white dress with cartoon animals on it. She asked us if we had boyfriends (Evyn, the same guy as last year, me, no, thanks for asking) and surprisingly did not tell us we got fatter, like usual. We just got complimented on how beautiful we looked, and Angelita even said to Evyn, “Listen to how good Sarah’s Spanish has gotten!”

We learned that back in December, Angelita had an injury scare. She was at the airport picking up her daughter who lives in Miami, when some guy with a luggage cart knocked her over. Being 80, her body took the fall pretty badly, breaking her wrist and knee. She has since recovered and no longer has a cast, but she can’t walk far. She says it seriously affected her day-to-day life, but luckily, she could manage still having guests with Silvino’s help.

We had barely been there 5 minutes when she was already asking us when we’d be back that week for lunch. She had plans to order us a veggie pizza from the same place she used to when we were students with her: Ring Pizza. Absolutely delicious. I had actually been talking about it earlier that day, recalling how she’d order Evyn and I each a full — not personal, FULL — pizza. We were excited to return.

She asked us if it seems that Cuba is different, if we like it as much as we did. Of course we still love it, we replied, and it certainly didn’t feel much different. Angelita lamented how the US government has been telling people not to come to Cuba, though it seems that talking to other Cubans, Americans still keep coming.

Having set dinner plans with Mitra, we had to depart. We said goodbye lovingly with intent to return.

Walking to the corner of 23 and 6, we breathed a contented sigh and prepared ourselves to hail a máquina (collective taxi). Pointing our fingers to the ground, the first máquina that appeared, a white Oldsmobile, pulled over and immediately agreed to take us to Coppelia, a landmark near Mitra’s. We couldn’t believe how easy it was, especially since people who look like tourists can get ripped off easily. I guess our clear knowledge of the system worked in our favor.

That night, we went to a nearby cafetería (cheap, local place). The evening air was pleasant. We split three dishes and got two desserts and two drinks for $5, total. If tourists knew how easy it was to get so much food for so little, they’d never spend time in Old Havana, tourist central.

Returning home, our friend Aldenis came to visit for a couple hours. He has dated another friend from our semester program, Lucy, since we arrived two years ago. Together, Aldenis and Lucy bought a car from 1940, supposedly owned by a famous jazz drummer. Aldenis has worked tirelessly for the better part of a year to restore it, removing its bright orange paint for a light blue in the process.

In his opinion, the car is one of the best ways to earn money in Cuba. He’s just no mechanic, so it takes more effort to get it in proper order. It took him about a year to get it up to speed. He was familiar with the world of cars, but this took him to another level.

We asked him what he thinks of the imbalance of earned salaries among Cubans — how drivers earn way more than state workers by gaining money from tourists. He said that yes, it’s unfair. Many people earning a state salary will engage in illegal activity to gain more money. That said, the car business isn’t necessarily secure, either — these cars could break down at any time. Moreover, drivers have to pay the state a lot of money for gas or petrol to get around.

Even though his car is completely ready to go, at age 20, he still doesn’t have his full license. Once he’s 21, he’ll be able to drive others around, but not tourists. That’s another 2 years. The car has to pass many tests to be qualified to drive tourists.

We asked him if thinks Cuba is changing, and he replied that he doubt it’ll change, at least politically. He likes Cuba, he feels safe here, and he doesn’t want to move. He has traveled — to Russia, South Korea — but doesn’t have grand travel plans for now.

By this time, it was 11:30 and had been a long day. It was time to sleep, but we felt good about our productivity.