Background

My original project proposal:

How can something continually influence a culture it directly contradicts? Last year, I was privileged to study Spanish in Cuba with Colorado College. I immediately became immersed in the lively culture – claves reverberating through streets, passionate salsa dancers in the clubs, and street artists displaying works of beauty and depth. One aspect of the culture that I truly did not expect to encounter, however, was that of American rock and roll. Cubans deeply resent the embargo the United States placed on their country in 1958, as it strangled Cuba’s access to resources. Virtually anything having to do with the United States can breed animosity or mockery among Cubans, but rock and roll stands apart. More importantly, the Beatles stand apart.

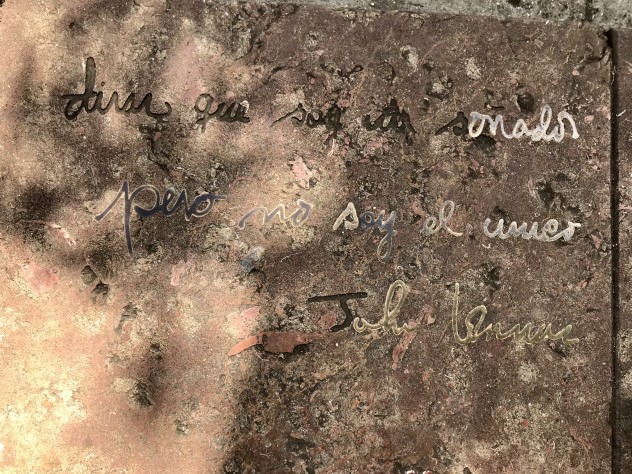

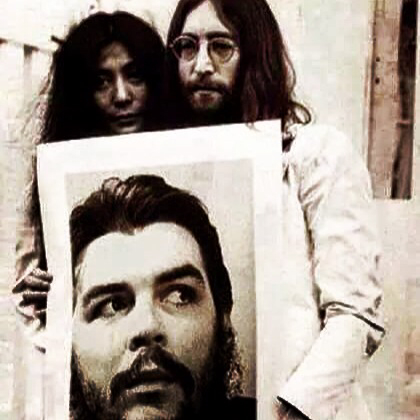

Just six blocks from my homestay, my roommate and I discovered a place like no other – “Submarino Amarillo,” (“Yellow Submarine”) – an underground, Beatles-themed bar. While the exterior of the bar was enough to make us, diehard Beatles fans, drool, the inside offered an even more incredible sight: middle-aged Cubans absolutely jamming to American rock and roll music, from Bon Jovi to Bruno Mars. Just next door to the bar lies John Lennon Park, complete with a bandstand modeled after that of Sergeant Pepper’s and a statue of Lennon seated on a bench. (The statue even has a pair of glasses that a designated park caretaker ensures is not stolen.) As we wandered the streets during our two months, paintings of Lennon also pervaded: some of Lennon alone, others juxtaposed with Cuban rebel Che Guevara.

I became fascinated by this Beatles culture. When the Beatles first emerged in Cuba in 1964, the Communist Party had been in power for just five years. Rock and roll had had a presence in Cuba since the early 1950s, from the strong media infrastructure – radio, film, newspaper, and television. About 90% of Cubans owned radios. To the youth, this media infrastructure represented liberation, non-conformity, and modernity, but to the elderly, it represented leanings toward US capitalism, decadence, and unlimited power. However, the elderly could not deny that media was attracting tourists, in addition to the casinos, hotels, and cabarets, all places that promoted American music. Frank Sinatra, Duke Ellington, and Nat King Cole were headlining in Cuban venues and American rock and roll dominated Cuban theatres. A Beatles cover band from 1965 to 1970, Los Pacíficos, also formed. Dressing like the Beatles and wearing similar hairstyles, the band adapted songs based on equipment available and performed in various locations in Havana: Teatro Musical, Teatro Universitario, and Teatro Martí (Valdes 128, in Los Beatles en Cuba). They eventually performed in the Anfiteatro de Marianao, a venue holding 5,000 listeners (Hernandez and Garofalo). In 1971, Cubans heard the Beatles over the airwaves for the first time (Volkert).

When the Revolution succeeded, Fidel Castro began consolidating private enterprise, taking control over the media. Soon, rock and roll became an enemy of the state, as the English lyrics and individualistic styles (long hair, bell-bottoms, miniskirts), contradicted Communist values (Volkert). Young boys particularly wanted to look like the Beatles, donning long hair, many rings, short petticoats, tight jeans and leather jackets (Soneira de Asprer 122-123, in Los Beatles en Cuba). Though these rock and roll supporters were now considered state enemies, however, many were also the young rebels themselves, who had fought to establish the new government. They argued that the long hair and jean jackets mirrored the style of Che and Fidel when they left the mountains to take control of Havana. Still, Castro feared their “American” spirit, and anxiety and suppression remained among Cuban rock and roll fans; in 1964, he banned all Beatles music, declaring it “mindless, vulgar consumerism” (Volkert, Morton). (Whether or not the Beatles, or rock and roll in general, were banned is still hotly debated.) In protest, Cubans would smuggle in tapes of “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” (Morton). Beatles tapes were distributed underground and Cubans tuned into rock and roll channels in secret.

Despite the government’s fear and repression of rock and roll, the Beatles presence remains in Cuba today, at least in Havana. Twenty years after “banning” Beatles music, for example, Fidel opened Parque John Lennon and changed his tune, saying: “What makes him [Lennon] great in my eyes is his thinking, his ideas,” he said. “I share his dreams completely. I too am a dreamer who has seen his dreams turn into reality” (Morton). In 1996, the Unión de Escritores y Artistas Cubanos held a colloquium for the Beatles specifically (Hernandez and Garofalo). And of course, as I saw myself, the image of the Beatles is not uncommon throughout the city. My project aims to examine this presence and how it has evolved. The Beatles in the 1960s represented rebellion, which corresponded to the Revolution, but also clashed with the regime it established. But what do they represent to Cubans today? To the youth, who did not participate in the Revolution, and to the elderly, who did? My goal is to talk to Cubans of all ages and learn what the Beatles means to them, why they think the Beatles are still relevant, and how they believe the meaning of the Beatles has changed throughout time.